Even though we know that errors are always present – and tend to multiply – there is very little information on error in architecture. Historical, theoretical and anecdotal discourses tend to focus on triumph-based narratives, on major achievements. We are obsessed with explaining the ways in which everything can go well, while we forget to explore the ways in which everything can go wrong.

As technology advances and becomes accessible to society at large, the illusion of perfection it seems to promise only increases the generalized frustration with the many errors we come across. Murphy’s Law has taught us that anything that can go wrong, will go wrong: we live with errors every day.

Speaking of error is to open up the possibility of thinking about human nature: we are clumsy, fragile, corruptible and makeshift. In the instrumental discourse of modernity, errors have become a sin and the control we try to exercise over them is equivalent to our frustration with our own imperfection. We are afraid of failure, but if we deny the imperfection of human nature, this fear will only increase.

As has been shown by the few specialists who have begun to address the issue of error in architecture, we can even construct a genealogy of modern architecture as a reaction to the fear of error. Instead of baroque spaces that are impossible to represent two-dimensionally down to the millimeter, as would be necessary for exact scientific measurements, modern architects and designers have utilized situations, spaces and objects where materials can be controlled with precision.

Clara Porset has explained how, in the 1950s, the ornamentation used on Mexican furniture was a way for carpenters to cover up the material errors of the artisanal construction process. Likewise, the theoreticians, architects and designers who defended and proposed the clean, abstract walls and elegant, fluid lines of Modernism repeatedly explained that their phobia of ornamentation was due precisely to the fact that ornamentations, moldings, capitals and finishes hid material errors, which they thought would be eliminated by industrialization and machine production – though we now know that this was not the case. Material errors are inevitable in the clash between the abstract project (and its pristine representation) and the material reality in which we live, no matter whether the construction process is artisanal or industrial.

Specialists in this issue speak of the absurdity of the obsession with precision that governs architectural discourse. There is a cult of precise details when cutting materials and joining them with others, as well as an excessive use of the word “precision” when critics describe the buildings they admire. This obsession with precision is clearly reflected in the software that we use to draw construction elements, which allows for ridiculous levels of precision, even up to eight decimal points, deliberately ignoring that these buildings will be built by the rough hands of construction workers on sites that have only been measured – in spite of all attempts to the contrary – to one decimal point, and then only temporarily.

The search for precision and the capacity to achieve it through advances in digital media can clearly be seen to be a simple illusion, just as the text or the geometric drawing once was. Current three-dimensional digital visualization media can even be seen as detrimental to the capacity for creative innovation, which is still thought of as being expressed through the freehand sketch: a pure space where ideas take shape. But it is worth asking if this is true: perhaps technological tools also help us creatively experiment despite – or because of – the physical distance from the computer; it is even possible that each glitch or “fatal error” that we come across in our interactions with these tools can be stimulating digressions that allow us to open doors to fields both treacherous and astonishing. Error can lead to more than simply frustration.

We shouldn’t ignore that the paradigmatic examples of modern architecture are also failures from certain points of view and that many have serious material errors: one particularly well-known case is that of Villa Savoye, in which water flooded the living spaces, but this example can also help us to understand there is no innovation without error, as it allows for the other meaning of ‘err’: something erratic, that deviates from the norm. The virtuous attitudes attributed to the genius of certain architects often turn out to be the result of this erratic process. Errors are valuable because they allow us to escape established norms, investigate unknown territories, understand the world in a different way and, above all, critically respond to the established order. A territory for error understood in this way has been acknowledged in jazz, in which innovation takes the lead and “errors” practically govern musical norms. We should ask what would happen in architecture if, understood in this way, error ruled our discourse instead of precision, or if we even accepted mistakes as a fundamental part of the process of the production of knowledge.

As a window on history, error can illuminate aspects that, from a perspective focused on heroic narratives, are practically invisible. The Candela concrete shells or the Mexican chairs that were to have furnished the United Nations headquarters show us the clash between the designer’s idealistically scientific plans (or at least as they are idealized by historians) and reality.

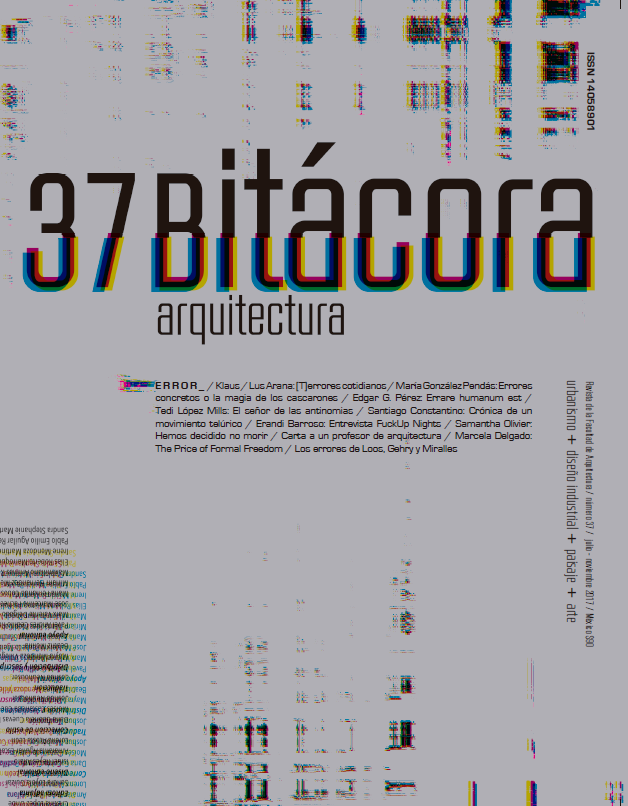

In this journal, at least since Issue #26 – when the new era began – we have argued that the editorial process is never free from error, and we embrace the liberatory power of expounding our errors on the traditional errata page. This has allowed us to redeem ourselves from the epic error of printing “desechos de autor” (copywaste) – instead of “derechos de autor” (copyright) – an incident we still remember with affection. We are certain that it is inevitable that we will continue making mistakes, despite all the care that we put into our work. We are not perfect, nor do we aspire to be.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/fa.14058901p.2017.37

Published: 2018-05-25